Jason Rezaian: Previously on 544 Days:

Ali Rezaian I knew that you weren't digging around into anything you shouldn't have been. You were following the rules.

Mary Rezaian: My fear was that you might have a heart attack or stroke because of the stress.

Marty Baron: I want to ask you how the Iranian government can justify imprisoning a good journalist and a good person.

Yegi Rezaian: I was like, what? I am going to be released. No, this is not what you promised me. What about Jason? They said we can't talk about Jason.

Jason Rezaian: They let Yegi go at the beginning of October, two and a half months after we were arrested. For me, it was a relief to know that my wife was no longer in that dungeon. Yegi had spent all of her time in Evin in solitary. 72 days. Now she was out, but she felt like she'd been released into a bigger prison. Our captors were holding on to her passport, so she had no way to escape.

Jason Rezaian: What were those first couple of weeks like after you got out?

Yegi Rezaian: Terrible. I know that I talk about it now very flat, like I don't get too emotional either way. Like not too sad or not too happy. Maybe that by itself is a manifestation of how much I hate those moments that I taught myself to control. And don't let those moments define the rest of my life. I really try to be normal because I didn't want to let those dark prison days affect me and who I was as if I was resisting to let those days leave marks on me and our life. But also, I didn't want my parents, I didn't want to disappoint them, I didn't want to worry them. The only times in those first two months that I left the house was any time that they called me and they said, I can come and visit you.

Jason Rezaian: We had some intermittent meetings where you could come and see me in those first couple of months. And at some point, um, I don't know how it happened that I started bringing letters that I wanted you to take out.

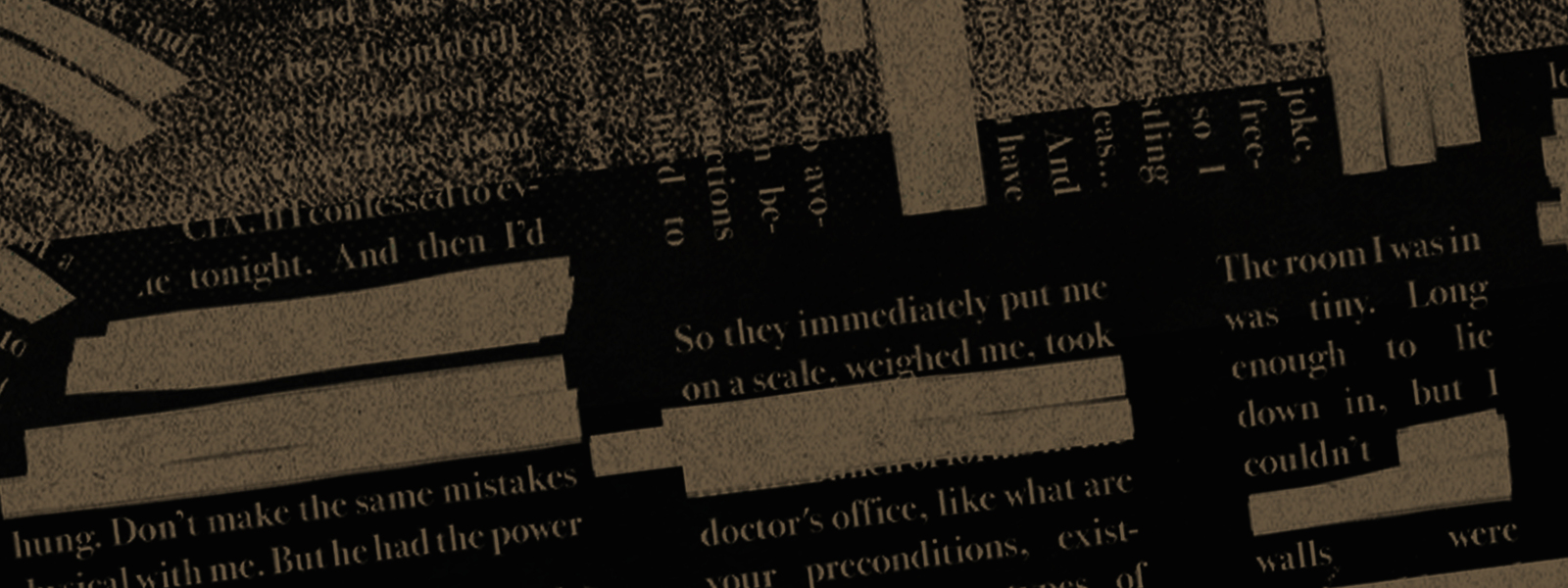

Jason Rezaian, narrating: I wasn't allowed pen and paper, but in prison, sometimes you find things you aren't supposed to have. And sitting in that cell, I had nothing but time to think about what message I wanted to get out about my situation.

Yegi Rezaian: You would pass on names to me and you wanted me to reach out to these folks and tell them to write about you in the news and say who you are and humanize you. Because what they were doing in Iran was de-humanizing you. You would write them and hide them in your socks or other places. And I would come in and every time they let me hug you, because I was wearing the chador, under the chador, you were able to pass it on to me.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: In Persian, chador literally means tent, and in its flowing folds, it was easy to conceal letters, except . . .

Yegi Rezaian: Except for that one time that I, I mean, you, you made a mistake. You left it in your shoes, so their camera got like a bunch of, like a tissue, like a ball of paper in your shoes.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: I'd gotten careless and left the letter in my shoes when I took them off. Not thinking anyone was watching, I went and got it.

Yegi Rezaian: And then you got it, like you got up. And in the middle of the meeting, went back to the door. You took it out of your shoes, you brought it in.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: They were watching. They were always watching. They confronted Yegi on her way out of the prison.

Yegi Rezaian: But then I gave it to them. I made a bad mistake. I should have just swallowed it down. I watched it in the movies many times. I don't know.

Jason Rezaian: They brought the note back to me the next day, and it was one where I was like, these people are assholes. And when, when they brought it, you know, it was like the main piece of actual evidence against me when, when I went to court.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Now, I'm told when Western hostages appear in Iran's Revolutionary Court, the judge sometimes pulls this letter out of a file and waves it at them. Don't be like Jason, he warns.

I'm Jason Rezaian. This is 544 Days. Episode 4. The Washington Post, the White House, and the worst Thanksgiving ever.

Wendy Sherman: We were all astonished that Iran would have imprisoned a Washington Post correspondent.

Sen. John Kerry: And believe me, we kept making that point. Everything was going to go to hell in a handbasket.

Mary Rezaian: If Jason had murdered somebody, it would be so much easier.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: When Yegi and I got caught passing notes, I lost what felt like the one tiny bit of control I had over my situation. She was the only source I could trust about what was happening outside the prison. Those scraps of information were the only thing that gave me hope. I mean, I was desperate to know what, if anything, people back in the US were doing to free me. I knew The Washington Post hadn't abandoned me. I'd seen Marty Baron questioning Iran's president on TV, but I had no idea the extent of their efforts, especially behind closed doors. I only found out later, those started almost immediately after our arrest, in late July 2014. The Post's foreign editor, Doug Jehl, was one of the first people to hear the news.

Doug Jehl: I had come out of the morning news meeting that happens every day at 9:30 a.m. and as I was walking back across the news from the foreign desk administrator came up to me and said, You've gotten a call. Jason's been detained. My heart began to pound.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: As you heard in the last episode, Doug called up my brother Ali. Then he and the other editors at The Post had to come up with a plan.

Doug Jehl: So the first question is, when do you say something publicly and what do you say? And we decided that we were going to say nothing for 24 hours, that we hoped that the Iranians would release Jason quietly. And we believed that to say something too quickly might simply cause the Iranians to dig in their heels. When we did say something, it was fairly neutral. We didn't want to be too loud and vocal and condemnatory. We felt like it was important to allow a face-saving way out.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: This is the initial response from almost everyone when someone they know gets taken hostage. It's based on the premise that the whole thing is just a terrible misunderstanding and it's the same conventional wisdom my mom and brother were told: if you speak up, the hostage-takers will double down. If you stay quiet, they'll come to their senses and let the hostage go. Often people will suggest that you have to let them save face. Save face! As if hostage takers give a shit about what anyone thinks. So at first, The Washington Post, as my employer decided to stay quiet, but as a newspaper, The Post had to cover my arrest. It was news. When a news organization itself is in the news, it can be a complicated. You have to create a separate editorial track, walled off from any private conversations. So that's what happened. They assigned the story just like they would any other piece of news. And they gave it to Carol Morello, who at the time covered the State Department.

Carol Morello: And so when you were taken, I was the logical person to write a story about it.

Jason Rezaian: Did you have any sense at that time that this might be a story that you would be covering for many months?

Carol Morello: Oh, at that time, I didn't have a sense. Nobody had a sense it would be for months or even weeks. Basically, my editor came over and said, Jason has been arrested, we have to write a story about this. I wrote a quick news story and figured I'd do a couple follow ups. And then eventually at some point, I would write the story of your release.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: It started to become clear that Iran wasn't going to quickly release me, so the Post stepped up its efforts. The paper's publisher got in touch with one of his contacts in the White House, Barack Obama's chief of staff, Denis McDonough.

Denis McDonough: You had your bosses at The Washington Post, which, as you know, they buy their meat by the barrel so you got to be careful with those guys.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: That's McDonough.

Denis McDonough: They were concerned about you and concerned that we weren't doing enough. They were, they were tough because they were worried about you. And I admired that, that they saw you as their guy and they were going to insist that everything be done for you.

Fred Ryan: That began a series of meetings where I went to the White House with Doug Jehl, foreign editor.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: And that's Fred Ryan, the publisher of The Washington Post.

Fred Ryan: In each case, we wanted an update. We wanted to know what was being done. We knew every time we asked for a meeting that there would be a round of preparation, there would be a series of updates, the requests would go out so that Denis and the people we met with could be briefed. And we thought every time we made that request, it would, it would light a little more of a fire under this. We wanted to find ways to make sure that it stayed front and center with the president, because if something's on the president's desk, that means there are a lot of people who are thinking about it and worrying about it and trying to find ways to solve it. And that's where we wanted to keep it.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Now, whatever you think about the media or the Washington swamp, you should know that it's not a regular occurrence for the top brass at The Washington Post to stroll into the White House for a chat with the president's chief of staff. It was so unusual that McDonough worried someone might notice folks from the Post on the White House visitor logs and embarrass all of them.

Denis McDonough: I said, look, I'm going to tell you guys everything that we're doing, but this has got to be non-reportable. It's got to be off the record. I have a policy of only speaking to reporters on the record. So that was different for me.

Fred Ryan: Those meetings were not reported. We didn't go back and give the reporters who were reporting on your case details that we had picked up at the White House.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: That means Carol Morello didn't know anything about these meetings. They had to stay off the record because they included sensitive information related to the nuclear talks. [sounds of applause] And talks like these were a high priority for Obama. He promised to change the way the country communicated with its adversaries.

[clip of President Obama] To those who cling to power through corruption and deceit and the silencing of dissent, know that you are on the wrong side of history, but that we will extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist.

Wendy Sherman: In his inaugural speech, he said if countries will unclench their fist, we will reach out our hand.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Wendy Sherman was the lead negotiator in the nuclear talks with Iran. She was one of the top people at the State Department under Obama, and she's now the number two State for President Biden. These talks were the biggest moment in the icy relationship between the two countries since they officially severed ties in 1980, over the hostage crisis. They were face to face, in public, for the first time in decades, with Sherman in the lead.

Wendy Sherman: First and foremost, I'm less Wendy Sherman then I was the United States of America, and the United States of America's pretty powerful position to have. I understood that.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: The U.S. saw Iran's nuclear program as one of the biggest threats to global security. Remember, Iran was part of George W. Bush's "axis of evil". And short of going to war, it seemed like there was no effective way to stop Iran from developing nuclear weapons. But now the U.S. was prepared to make major concessions to the Islamic Republic—like lifting a lot of sanctions—in exchange for strict limitations on Iran's nuclear program. The talks were never going to be easy. By the summer 2014, both sides had a general idea of a final agreement, but negotiations dragged on. They set a deadline to reach an agreement by July 20th. So that month, Wendy Sherman went to Vienna. I went too, to cover the story. They held the meeting at this massive white palace in the center of the city that's now a luxury hotel here.

Wendy Sherman: We were in Vienna at the Palais Coburg. Huge portraits of Austrian royalty from the past hanging over walls with ornate filigree and royal blues and gold. Quite a strange place to be having such a negotiation, but it provided a lot of security. And in the basement was this cavern, which actually was in part a wine cellar. Also another very strange place to have a meeting where Iranians might be present, because, as you know, it is a conservative Islamic society and alcohol is prohibited.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Actually, there were a whole lot of things the Iranian delegation wasn't allowed to do. But American diplomats are more flexible, which is an advantage.

Wendy Sherman: I couldn't shake hands with these gentlemen because of the difference in religion and culture. So I put my hand across my chest and nod. If you're in a room full of men, you look like a Marx Brothers routine after the first five minutes of doing that. So during one break, I told them that I had grown up in a Jewish community, that I was Jewish, which they already knew, and that, of course, I didn't put out my hand because I never knew whether a man was an Orthodox Jew and therefore wasn't going to shake my hand. It was a very strange conversation talking about Judaism to men from a country who believe that Israel should be wiped off the face of the earth and the Holocaust never happened. But it was a useful conversation. And although we continued to be tough as nails in the negotiating room, it's helpful to see each other as human beings as well.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Covering these talks was the first time I'd gotten to travel to another country to report an Iran story. It felt like a huge step in my career.

Wendy Sherman: And you, as part of the press, could be outside on a plaza that was in front of the hotel, but still a barrier to the hotel. So you could have proximity and we could have security.

Jason Rezaian: It's exactly how I remember it. The only thing that I would add is $15 cappuccinos in the lobby bar, which any hack on a very limited per diem could never forget.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: So for more than two weeks in July, the delegations met at the Palais Coburg.

Wendy Sherman: That two weeks was quite extraordinary. We actually had seminars where different countries took the lead in discussing different elements of what we knew would have to be in a deal. So the United States did a seminar for everybody, including the Iranians, on centrifuges, and the Germans on transparency techniques, and the Russians on plutonium reactors. It was a way for us to both get to know each other, make sure we all understood what we were talking about, what with all the elements were.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: In the end, they didn't complete the agreement, but it seemed like things were moving in a positive direction.

[news clip] What's happening in Iran, it just agreed, along with the U.S., to extend negotiations over its nuclear program for four more months. That's after missing the July 20th deadline for a comprehensive agreement, one that would—

Jason Rezaian, narrating: From covering the talks. It was pretty clear to me that it might take a while, but the deal was going to happen. After the meeting was over, I went back home to Tehran. Three days later, Yegi and I were arrested.

Wendy Sherman: We were all astonished that Iran would have imprisoned a Washington Post correspondent. Do they not understand that The Washington Post is not going to sleep until Jason Rezaian and Yegi Rezaian are free?

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Everyone on the U.S. side figured that our arrest had something to do with the nuclear talks, including Ben Rhodes. He was one of President Obama's top foreign policy advisors.

Ben Rhodes: I remember just sitting there and thinking, fuck, this is going to be an enormous challenge, that they'd never gone this far before. And frankly, I remember thinking, well, maybe the Iranians just want to blow up this thing.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Iran already had a long history of taking hostages to promote its interests, and the White House knew there were factions inside Iran that didn't want the nuclear deal to happen. A lot of politicians in America didn't like the negotiations either.

[clip of Tom Cotton] And many senators and many congressmen, Democrats and Republicans alike, have grave concerns about the path that the president has taken us down.

[clip of Sen. Mitch McConnell] The Iranian regime has carried out its best attempt at a charm offensive to forestall even tougher sanctions.

[clip of Sen. Gardner] Well, if the entire purpose of keeping Iran from getting a nuclear weapon was the real outcome of this, then we would be doubling down on our sanctions until they said we will not try to achieve a nuclear bomb.

Ben Rhodes: Congress is constantly agitating to impose new sanctions on Iran, even during the negotiation, And not just Republicans, Democrats as well. And so every time the negotiations didn't succeed and had to be extended, or every time an external event took place that highlighted the malevolence of the Iranian regime, I knew I was going to have to fight off the imposition of new sanctions, which could blow up the whole negotiation.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: The Obama administration didn't want to let the most obstinate factions in Iran OR the hawks in Congress get their way. But they knew Iran was holding Americans for leverage: me, a pastor named Saeed Abedini, and a former Marine, Amir Hekmati. They were going to have to figure out a way to get us out, without rewarding Iran for taking us hostage.

Wendy Sherman: What precedent are you setting? Will you incentivize Iran to take more Americans prisoner?

Jason Rezaian, narrating: That's Ambassador Sherman again.

Wendy Sherman: Will you set a precedent for what happens in the rest of the world? What do we owe to people like Jason Rezaian languishing in Evin prison? And the president was really clear. He wanted to do whatever we could to move this forward.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: They knew one thing for sure. If the U.S. team wanted to get me and the other Americans out of Iranian prison, they had to keep us out of the nuclear negotiations.

Wendy Sherman: We tried to keep the two separate for a very fundamental reason. If we put them together, we would have given Iran more leverage. They would have thought that they could use you as a pawn in the negotiations, or vice versa, that we would be tempted to play one against the other.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Sounds clear enough, but separating the two would prove incredibly complicated. Don't forget, it's not like the US and Iran talk to each other all the time. These were their first major discussions in decades. If this deal got signed and freeing me wasn't a part of it, it seemed pretty likely to me that I wasn't going anywhere. This moment was my only chance. From the outside, the idea of separating the nuclear talks from the prisoner negotiations just seemed silly. They're saying that the U.S. wouldn't let Iran use hostages as leverage, but from the perspective of The Washington Post, it seemed obvious that it already happened.

Doug Jehl: What had became clear was that, in fact, Iran was doing what we were afraid they were doing, which was essentially to take an American journalist hostage to secure their foreign policy interests. And that was really alarming.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Coming up, the efforts of the Obama administration, and my mom, begin to intertwine.

Jason Rezaian: By late November, I'd been in prison for four months, and as far as I knew, the Obama administration wasn't doing anything to get me out. But then something happened. On Thanksgiving morning, my interrogator Kazem came to my cell with a message, he told me I had to call my mom. Why? I asked him. Today is a holiday and you must congratulate her, he said. It is the Great Judge's gift to her. Your mother wants to hear your voice. I didn't like the idea. Not that I didn't want to talk to my mom. I hadn't been able to speak to her or anyone other than Yegi since my arrest 128 days earlier. But I was suspicious of the sudden largesse on the part of the Great Judge. Kazem handed me an old Nokia cell phone. I didn't have a choice. My mom was expecting the call. She was in Chicago at her cousin's place. It was early in the morning, their time. Thanksgiving. Turkey had just gone into the oven.

Mary Rezaian: One of the first things you told me was that there were people with you. And they wanted you to, they wanted ME to know that you were not being held in prison, that you are being held in detention. That seemed a little bizarre. But I knew that you had people around you and that we wouldn't really have the freedom to talk about anything. So we talked about family and we talked about past Thanksgivings together. And you told me you were really tired, and you hadn't done anything.

Jason Rezaian: Right. I hadn't done anything wrong, and I'd been sitting in prison, doing nothing for four fucking months.

Mary Rezaian: And we just kept talking for about a half an hour. While we were talking, I kept thinking, boy, this call is really, I mean, he's being allowed 10 minutes, 20 minutes, 30 minutes.

Jason Rezaian: Yeah. Felt like a really long call.

Mary Rezaian: It felt like [laughs], it was like, wow, this is great. And what's going on here? You know?

Jason Rezaian: Yeah. I got to a point was like, I really don't have much more to say.

Mary Rezaian: I think maybe you probably verbalized that and I probably did too. And maybe we thought that would be extra minutes on the card that we could use at some later date.

Jason Rezaian: What about my mental, kind, of state?

Mary Rezaian: I felt you were really holding things together well, but I know you and when you get to a point after a long period of time of putting up with something, then suddenly you stop. And I was concerned that it was getting to be that point. And this had been, what, three, four months into it? We had no idea how long it was going to go on beyond this.

Jason Rezaian: I mean, once you got me on the line, were you, were you more or less worried?

Mary Rezaian: I think I was more worried. I knew you were upset. I knew you were frustrated, I knew you were angry. I knew you felt this was really unjust, and that that weighed very heavily on you.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: What I remember most clearly about that phone call with my mom was wondering why it was happening at all. I've been held for four months in prison, no contact with my family back home. I've been told they all thought I was dead, that my mother was sad but she'd gotten over it. Now, all of a sudden, I was given time to talk to her. Not just a little bit of time, actually, kind of too much time.

Mary Rezaian: And then I got a call from Ali. It was a very brief call and he said, Mom, the house is going to receive an important telephone call. The phone call came and it was a young woman's voice telling me that Secretary Kerry would like to call and speak with me, which put the household in a tizzy.

Sen. John Kerry: So we were deeply, deeply invested in freeing you. I mean, the idea of a wrongful imprisonment, the idea of somebody rotting away in a cell and getting sick, that is not a healthy place.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: That's John Kerry.

Sen. John Kerry: And we knew what the conditions were like and we knew what your health was like. And the last thing in the world we wanted was to see you pass away under those circumstances. And believe me, we kept making that point to the Iranians. If that did happen, everything was going to go to hell in a handbasket.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Turns out Kerry had negotiated with the Iranians for that Thanksgiving call, and the point of it wasn't to my mom and I could have a nice holiday chat. The point was to test the Iranians. Could they, would they deliver something that the US was asking for, something as small as a phone call?

Sen. John Kerry: How do we prove we're going to be trying to move in the same direction? We want to know that Jason's OK. He's gotta, you know, his mother needs to talk to him. She's living in agony. We got to try to, you know. And we just thought it was the humanitarian way of beginning to establish some kind of a process that could at least create that kind of transactional moment.

Mary Rezaian: And he asked how you sounded. And I said I thought you sounded surprisingly well, given the circumstances. But I also told him that you had other people in the room with you. And then Secretary Kerry assured me that he was working toward your release. And we ended the conversation. It was quite, quite brief. And I thanked him for his efforts.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: My mom's takeaway from the conversation was that finally someone with some juice was on the case.

Mary Rezaian: It felt really good to me that on such an elevated level in our administration that you were getting some attention, because your concern during those early months was that nobody knew what was going on. It just, it felt very good.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: What happened next was set in motion by the call I had with my mom on the phone, I asked her to come to Tehran. I knew the authorities wouldn't deny her right to come visit me. If they did, it would look very bad. Mothers have a lot of sway in Iranian culture. It seemed like if anyone was going to really be my voice, they were going to have to do it from inside Iran. And my mom was the only person who could pull that off.

Mary Rezaian: What you didn't know was that from the earliest weeks after it became obvious that we weren't going to be able to find somebody on the inside to make this go away, I was telling Ali that I felt it was really important to go, because not only did I have a current Iranian passport, which I needed to have because I also in the dual citizen and I wouldn't be allowed into the country on an American visa.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Being a dual citizen meant that my mom could come and go from Iran like any other Iranian. But Ali didn't like the sound of this plan.

Ben Rhodes: She's like, well, I want to go to Tehran. And I said, I really don't think that's a great idea. You know, I think the idea of giving them somebody else to harass was not something that I wanted.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: But if your son who's stuck in prison asks you to come, you come.

Mary Rezaian: I realized that things had changed and that I was about to step into a much more active role. Up to that point, Ali had been handling things while I was in Turkey and now I had told you that I was going to be making every effort to come and be there and meet with authorities there.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Mom arrived in Tehran in December. One of her first moves was to schedule a meeting with a relative of my dad's, a guy who was very influential. She traveled to Mashhad, dad's hometown, and the relative met her in a back room at Iran's holiest shrine. Picture the Shia equivalent of the Vatican.

Mary Rezaian: And we were brought to a very large hall and there was between 16 and 20 men, and me. As I was sitting with these men in this very ornate room with someone serving us tea, dad's contact said to me, you know, Jason has been accused of a very, very serious national security crime. If Jason had murdered somebody, it would be so much easier for us to make this go away. But because of the crime that he is accused of, it's out of our hands. We can't do anything about.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: In Iran, the life and death of an individual has a lot less meaning than the survival of the regime. That's why, whenever I asked my captors to detail the charges against me, they always evaded the question. They'd say, you're charged with very serious crimes. Oh yeah? What crimes are those? They're so serious we can't even tell you what they are. So serious, they don't even have names. Secret crimes. It was like being trapped in a Kafka novel. From the moment she hit the ground in Tehran, my mom started petitioning the authorities to allow her to visit me in prison. That was her right as a mother. They could only put her off for so long. So a few days before Christmas, she got a phone call.

Mary Rezaian: On the 22nd at 9:30 in the morning, the phone rang and Yegi mother took it and she was quite upset. She said to me, They want to see you at 11 o'clock.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: It wasn't entirely clear who THEY were. Yegi's mom had some pointers for my mom on how to act when summoned to this kind of meeting.

Mary Rezaian: Before leaving the house, her mother instructed me that I was supposed to be very contrite, and cry, beg for mercy for you, pretend to faint.

Jason Rezaian: A whole bunch of things you weren't going to do.

Mary Rezaian: A whole bunch of things that I knew I could not pull off to save you! I would have tried it if I thought I could have could have saved you that way. But I thought, no, this, this doesn't this doesn't square with the person that I am.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Yegi decided to go with my mom for support and to help translate. They got in a cab. The whole way there my mom was thinking, could she act like the contrite Iranian woman Yegi's mom told her to be, crying and fainting. She had to decide.

Mary Rezaian: How to deal with this, you know, how can I pull this off? And I'd spent hundreds of hours watching Turkish Novellas, you know, like seeing soap operas. And some were about Turkish matriarchs. And during this interval of time, I made myself a plan that I was going to become a Turkish matriarch.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Apparently, you have to watch Turkish soaps to really understand the power of the Turkish matriarch figure. But suffice it to say, she's not about to start crying and fainting and begging for mercy.

Mary Rezaian: So we were ushered into this building with cameras on the outside, and there were a couple of guys, and one of them said to me in English: we saw you on TV, we saw you on BBC, why did you go there? And I said: because this is taking too long, my son is innocent and I want to see him. And we had a back and forth and I was pounding on the table. And I'm looking him straight in the eye, which I know Iranian women of my age would not do. So I wasn't playing the part that they expected me to play.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Mom still didn't know exactly who she was talking to. She figured these guys belong to Iran's judiciary.

Mary Rezaian: One of them said to me: the judiciary allows us to use these rooms. And I was thinking, OK, so who are you guys? I mean, I didn't say that, but I probably had a quizzical look on my face. So I figured out, OK, black shirts, masks, they must be part of the Revolutionary Guard. I'm glad I didn't put that all together before I walked in the room and tried to act like a Turkish matriarch because I not have been as effective pulling it off. [laughs]

Jason Rezaian, narrating: The Turkish matriarch routine was effective. They promised she'd be able to see me by Christmas. Of course, with these guys, promises don't mean much. But my mom passed her first big test. She'd stared down the IRGC, and they'd blinked.

Jason Rezaian: Coming up on the next episode:

Wendy Sherman: I say this with an uncanny kind of respect, he's a terrific drama queen.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: The nuclear talks heat up.

Finer: One minute he could be low key and the next minute, high drama and pounding the table and shouting.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: And the US starts secret talks with my captors.

McGurk: If you ever find yourself in an empty basement somewhere strapped to a chair with a light bulb over your head, you don't want to see that guy walk in the room.